It seems like a distant dream sometimes, as Fox News stirs up dark passions and Sunday pundits trade blows, to consider a public space where all ideas are welcome. That’s what Kathy McLean and I had in mind, though, when we started to work on a book called Visitor Voices in Museum Exhibitions.

We were both of the anti-war generation, when that meant Vietnam, and we’d both grown up with parents involved in the spy business. Those experiences had made us doubly conscious of how domestic surveillance had eroded free speech (if you don’t believe it, read The Burglary or watch the film 1971) and perhaps more fierce than most in our advocacy of civic spaces where all speech is welcome.

The idea of a museum as a vital community resource and place for free expression wasn’t new. Newark’s John Cotton Dana had advanced the idea a century earlier of a museum that is a “natural product of the community in which it appears.” Programs and events were able to adapt more fluidly to changing communities and changing times. But what about exhibits?

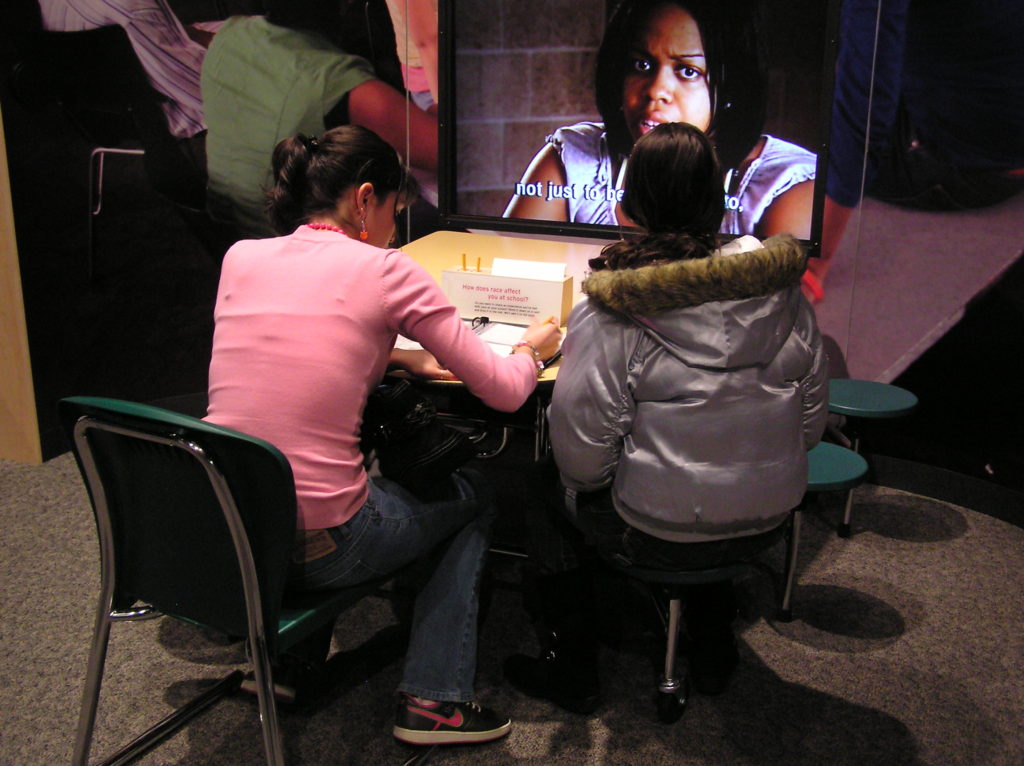

We wanted to inventory approaches museums were taking and think about what we were learning. Methods for including visitors’ voices in exhibitions were often crude, we found, and, in retrospect, even naive: Here’s paper and pencil: tell us what you think. Still, the conversation seemed a worthy counterbalance to the rising tide of blockbusters and corporate sponsorships. Didn’t a heartfelt handwritten message somehow carry as much weight as a slick exhibition about the Titanic sponsored by Clear Channel? (In this area of the Science Museum of Minnesota’s exhibition RACE: Are We So Different? visitors write reflections on a film made by teens called “Where do you sit in the cafeteria?”)

Possibilities for making your voice heard multiplied with the spread of what once were new media, and boundaries blurred between museum and world-outside-the-walls. A curtained booth at San Francisco’s Exploratorium, where people could record their musings about love, was soon echoed in StoryCorps’ freestanding installations, and a Soundcloud plug-in let Ken Burns invite viewers to record their own families’ Dustbowl histories.

Possibilities for making your voice heard multiplied with the spread of what once were new media, and boundaries blurred between museum and world-outside-the-walls. A curtained booth at San Francisco’s Exploratorium, where people could record their musings about love, was soon echoed in StoryCorps’ freestanding installations, and a Soundcloud plug-in let Ken Burns invite viewers to record their own families’ Dustbowl histories.

It was this same spirit that led me to incorporate a community story project into an NSF-funded media project about trees. During 2013-16, while a filmmaker worked on a traditional documentary series, Anna Hiatt and I traveled the country to record short first-person stories with people who were working with trees in their communities. Rather than waiting to ask them to respond to the series as it aired, we invited them into the process in advance. We took cues more from journalistic practice than museum tradition, and the space we made had no walls. But we hoped to honor the work and the wisdom of our fellow citizens, capturing their voices and bringing them to the attention of others. The series hasn’t aired, but we shared the stories as we completed them, and you can watch some of them on our site citizenforesters.org.